Chapter One - Badge of Truth

November 13, 1954, began like most fall mornings in the hills of West Virginia. Frost clung to the porch rail, and the smell of last night’s coal fire drifted from neighboring homes. I was twelve years old then—old enough to sweep dust from the floorboards, but still young enough to tug at Mama’s dress whenever Papa stayed home from work.

The sun hung low behind the mountains, casting pale light across our main road. Beneath those ridges, danger churned where Papa and nearly every man we knew earned their living. Coal dust found its way into our curtains, our collars, even the pages of Mama’s Bible if she forgot to keep it wrapped.

Tugging on Mama’s sleeve, I whispered, “Why is Papa still home? Wasn’t he supposed to be working?”

“He isn’t feeling well, dear,” she said, steadying her cup so it wouldn’t wet the tablecloth she’d laundered by hand just yesterday.

A boom shook the windows—louder than thunder, unmistakable in a mining town. Mama gripped the table as her tea sloshed. Papa, who had been lying on the couch with his eyes shut, shot upright as if the blast came straight through his bones.

“Where are my boots?” he barked, stumbling toward the door. He nearly tripped over them. “Never mind—I’ve got them.” Without tying a lace, he ran outside. The screen door slammed shut behind him, its spring squealing in protest.

I stood frozen at the window long after Papa disappeared down the road, unsure whether to breathe or pray. Mama pressed her hand to her mouth, staring toward the holler where the mine lay hidden beneath the earth. We said nothing. Silence told us more than words ever could.

The collapse of Mine No. 9 hollowed out our community. Folks said you could hear the mountain groan before it fell. Papa took the loss hardest. I’d never seen him or Mama mourn outright, yet the porch grew quieter each night—his pipe hanging longer between puffs. Men didn’t talk much about grief where we lived; they simply sat longer in silence.

A few weeks later, we packed what Mama called the pieces of our life. She wrapped her teacups in last winter’s newspaper. Papa tied down the washboard, sewing machine, and coal scuttle in the back of Mr. Rogan’s truck. Quilts, jars of canned beans, a tin of lye soap—everything rattled as we traveled the mountain road toward another mining town—Coalburn Hollow—where my best friend Rachel lived. Our boxes were heavy with memory and the thin hope of a fresh start.

At our new home, evenings settled into routine. Mama kept busy at her treadle sewing machine, its steady rhythm filling the kitchen as she stitched me a winter coat to replace the one worn thin at the elbows. Papa found comfort the way most men did—sitting on the porch steps with his pipe, watching dusk settle across the ridge. Lantern light from neighboring windows glowed like small constellations scattered through the holler.

The wool Mama worked with smelled faintly of lavender sachets from her drawer, mixed with the sharper tang of freshly dyed cloth. I loved rummaging through her sewing scraps; every remnant felt like a piece of some hidden story. Mama said I inherited her curiosity. Lately her hymns drifted slightly off-key. She blamed the dampness, but something deeper trembled in her voice.

One cold morning, she handed me the finished coat. “There you are, Abigail,” she said, unusually formal. “I used black and brown wool so the coal marks won’t show so quick.”

“Thank you, Mama.” I hugged her, breathing in lavender, starch, and the faint sweetness of cherry tobacco that lingered in the room.

“Can you put away the sewing materials?” she asked, rubbing her temples.

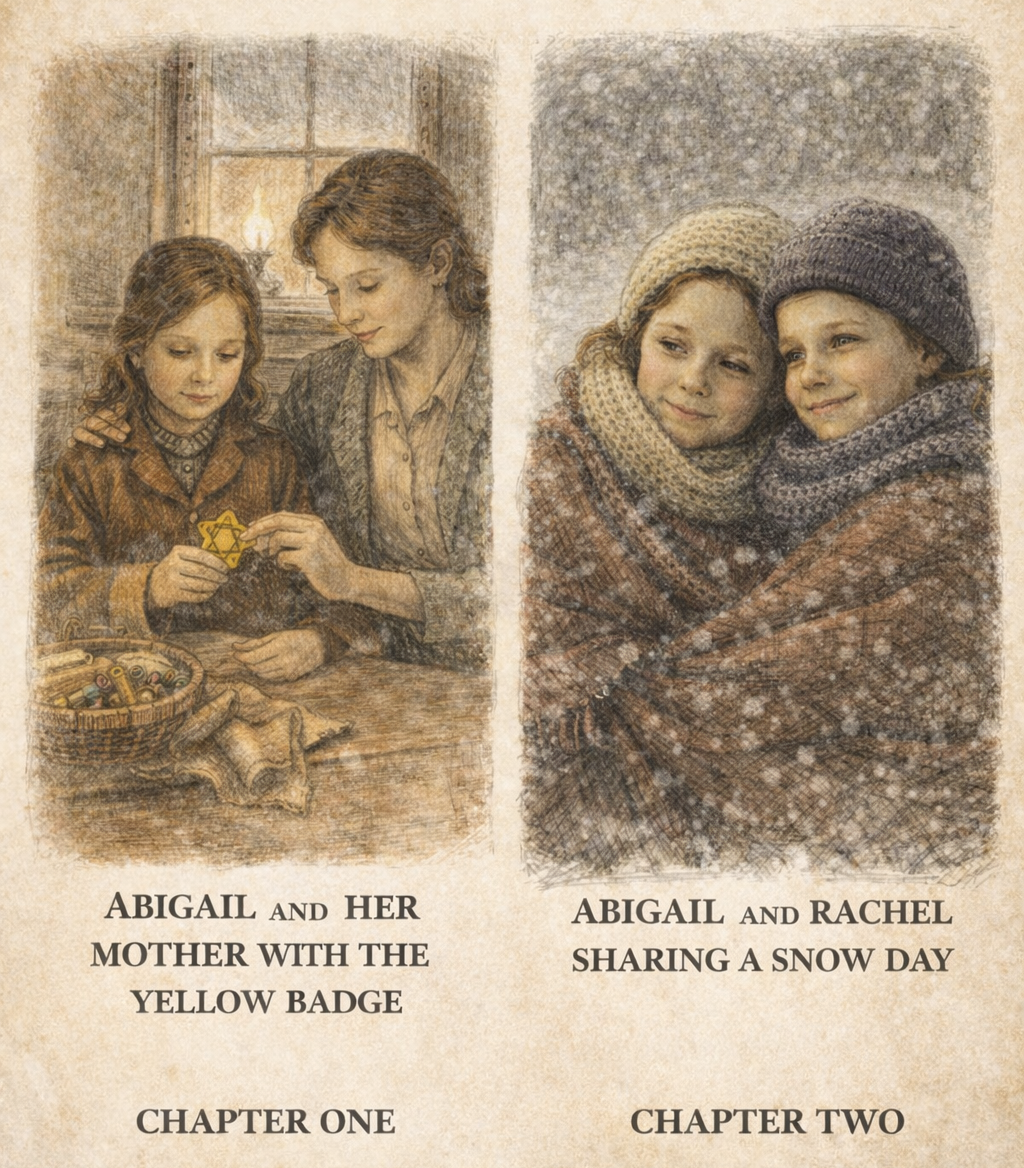

I reached for her wicker basket, careful around the treadle machine. My fingers brushed something stiff beneath folded flannel—rough and unfamiliar against the soft cotton. I lifted a small cloth badge.

“Mama, what’s this?”

Yellow thread outlined a six-pointed star. It rested in my palm, simple and quiet, as if it remembered something heavy.

Mama’s hand froze midway to her cup. Color drained from her face. She turned toward the fogged window, listening not to the world outside, but to something long held within herself.

“We became your parents,” she whispered. “When you were an infant. Your birth parents couldn’t care for you after the war.”

She paused. Folks didn’t speak openly about sorrow where we lived; grief stayed in the corners of rooms.

“Things happened far away,” she continued softly. “Families torn apart. Children hidden. Your parents were prisoners who never came home.”

“That star belonged to your people,” she said. “It marked them—who they were, and why they were hunted.” Tears welled in her eyes. “That terrible man, Hitler, marked them for destruction.”

She reached for her Bible and opened it carefully, as though it might break. From between Psalms and pressed flowers, she removed a worn photograph. Two young faces stared back—hopeful, soft, unaware of the darkness waiting beyond the edges of that moment.

“Did you meet them?” I asked.

“Yes,” she breathed. “A long time ago. Your mother was my childhood friend before I came here.”

I traced their faces with my thumb. “Mama, I love you and Papa,” I said quietly. “But my heart aches for something I never had.”

The scraps in her sewing basket carried a different weight then—threads of survival and belonging stitched into a child’s coat.

“Please put away the badge,” Mama murmured. “It’s a reminder of sorrow best left folded away.”

I hesitated. Then I placed the yellow star back into her trembling palm.

“Mama,” I said, my voice small but steady, “will you sew it onto my coat?”

She resisted at first. Then she nodded.

Her hands shook as she stitched the badge to the right side of the coat. The needle flashed in the lamplight—tiny sparks disappearing into wool.

“Why didn’t you tell me sooner?” I asked.

“Sweetheart,” she whispered, pulling me close, “we only meant to protect you.”

I pressed into her shoulder, breathing in cherry tobacco and lavender. Outside, the hills stood quiet and watchful. Inside, something settled into place.

I did not know what this truth would ask of me in the years ahead. I only knew it was mine now—stitched where it could be seen, carried where it could not be denied.

Chapter Two - Snow Day at Coalburn Hollow

Snow came in the night, soft and certain, sealing Coalburn Hollow beneath a hush that felt almost holy. By morning, the ridges stood blurred and white, their sharp edges gentled. The mine whistle never sounded—too much snow on the road to the tipple for the morning shift. Papa stayed home.

That alone made the day feel unreal.

Mama woke me early, though there was nowhere to be. “Look,” she whispered, pulling back the curtain. Snow pressed against the window like breath held too long. The yard was unmarked, the road vanished. Even the coal bins looked kinder under their caps of white.

Papa sat at the table in his wool socks, hands wrapped around a mug that steamed the chill from his fingers. His boots rested untouched by the door.

“Mine’s closed,” he said simply, as if saying it too loudly might change its mind.

Mama set about breakfast with a lighter step than usual. The skillet hissed. Coffee filled the room with warmth. Outside, the world seemed to have agreed—just for today—not to ask anything of us.

Snow days always felt borrowed in a mining town. They postponed danger, not erased it. Still, Papa lingered. He read the paper slower. He laughed once when the stove popped. The sound startled all of us, like a bird taking flight indoors.

After breakfast, Mama sent me to fetch kindling from the shed. The cold bit sharp, but the snow squeaked under my boots in a way that made me smile. I filled my arms until they ached and hurried back inside, cheeks burning.

By midday, neighbors’ children drifted toward our yard, bundled and red-faced. Sleds appeared from nowhere. We took turns tumbling down the slope behind the house, landing in laughter and powder. Snow found its way into collars and mittens and hair, but no one minded.

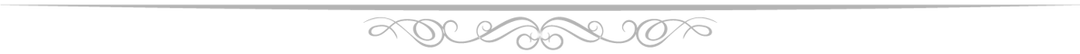

Rachel slid in beside me at the top of the hill, brushing snow from her sleeve. She bumped my shoulder hard enough to knock me off balance.

“Jewish or Baptist or Martian,” she said, grinning, “you’re still my best friend."

I laughed, the sound bright and surprised as we pushed off together, the sled skimming fast and crooked toward the bottom.

Papa watched from the porch, pipe unlit between his fingers. He called out once—Careful now—then stopped himself, as if realizing the word didn’t belong to this day.

Inside, Mama stitched at the sewing machine, its steady rhythm keeping time with the snowfall. She hummed a hymn I half-recognized, the tune steadier than her voice had been in weeks. The sound settled me.

By late afternoon, the light began to fade. Snow kept falling, tireless. Papa shoveled the steps twice, though there was nowhere to go. Each scrape felt ceremonial.

Supper was simple. Beans. Bread. The kind of meal that warmed more than it filled. We ate close together, knees nearly touching. Outside, the hollow held its breath.

That evening, Papa took down the lantern and lit it, though the power was still on. “Just in case,” he said, hanging it by the door. The flame glowed soft and forgiving.

When night came fully, the snow finally slowed. The world beyond our windows lay buried and still. Papa stretched out on the couch, hat over his eyes. Mama folded laundry by the fire. I sat on the floor, watching the lantern sway slightly when the house settled.

Nothing was solved that day. The mine would reopen. The mountain would remember. But for those hours, danger stood at a distance, quieted by weather and grace.

Before bed, Papa stirred and said, half-asleep, “Good snow today.”

“Yes,” Mama answered.

I carried that with me as I climbed the stairs—the knowledge that safety can arrive without warning, stay for a while, and leave without explanation. And that sometimes, for one winter day in Coalburn Hollow, that is enough.

Chapter Three - Our Run-of-the Mill Evening

Rogan came by just before dusk, Buddy trotting ahead of him like he’d been invited first. The dog cut across the yard without slowing, already home in a place that wasn’t his.

Papa was out back splitting kindling. I heard the ax pause before I heard Rogan’s voice.

“Paul,” he called. “Thought you might still have my brace.”

Papa leaned the ax against the stump. “You’re welcome to grab it. Left it on the porch.”

Rogan nodded, the motion small, as if words were something to be used sparingly. Buddy sat when Rogan stopped, though his eyes never left me. I didn’t realize I was humming until Buddy’s ears twitched in time with it.

Mama wiped her hands on her apron and stepped onto the porch. “Rogan,” she said. “You’ll stay for coffee.”

He hesitated. Mama didn’t wait for an answer.

Rachel came running from around the side of the house, cheeks red, hair free from her toboggan. She skidded to a stop when she saw me.

“You coming?” she asked.

I adjusted my hat and followed her toward the creek path. Buddy rose at once, glancing back at Rogan.

“Go on,” Rogan said.

Buddy didn’t need telling twice.

The creek was low and clear, the stones visible beneath the water. Rachel hopped across them without thinking. I took my time, testing each step. The helmet felt heavy and steady on my head, the strap hanging loose against my face.

Rachel turned and squinted at me. “You going to wear that forever?”

I stepped onto the far bank. “Maybe.”

She laughed. “You wore it yesterday.”

I didn’t answer. The water made a soft sound as it moved past the rocks, and I hummed along with it without meaning to.

Rachel stopped smiling. “You’re doing it again.”

“Doing what?”

She listened. “That.”

I stopped. The soft noise of flowing water rushed in where the sound of my humming had been, and it felt like I was standing there without a piece of me.

Back at the house, Papa and Rogan stood close together at the table, heads bent over the brace. They didn’t speak much. They didn’t have to. Mama poured coffee and set out a plate of bread she’d warmed on the stove. She pressed a napkin into Rogan’s hand without looking at him, the way she did for Papa.

Rachel sat beside Mama, swinging her feet. Mama gently brushed her hand against Rachel’s hair, the motion practiced and easy. Rachel leaned into it without noticing.

Buddy lay down where the table’s shadow met the sun, one eye open, always watching.

Papa tightened the brace and handed it back. Rogan weighed it in his palm, nodded.

“Good,” he said.

Mama touched Papa’s shoulder as Rogan stood. “Take a loaf of bread with you.”

Rogan didn’t argue. He wrapped it carefully, like it mattered.

When they stepped outside, Buddy followed halfway, then stopped. He looked at Rogan. Then at me.

Rogan sighed. “You and Rachel, be home before dark.”

Buddy looked at him once more, then came and sat at my feet.

I didn’t know why that felt important. I only knew it did.

Mama called Rachel in to help her with supper. Papa went back to the woodpile. The hollow settled around us, quiet but awake.

I rested my hands on the rim of my hat and hummed again, soft enough that even I couldn’t quite hear it.

Buddy’s tail thumped once against the porch step.