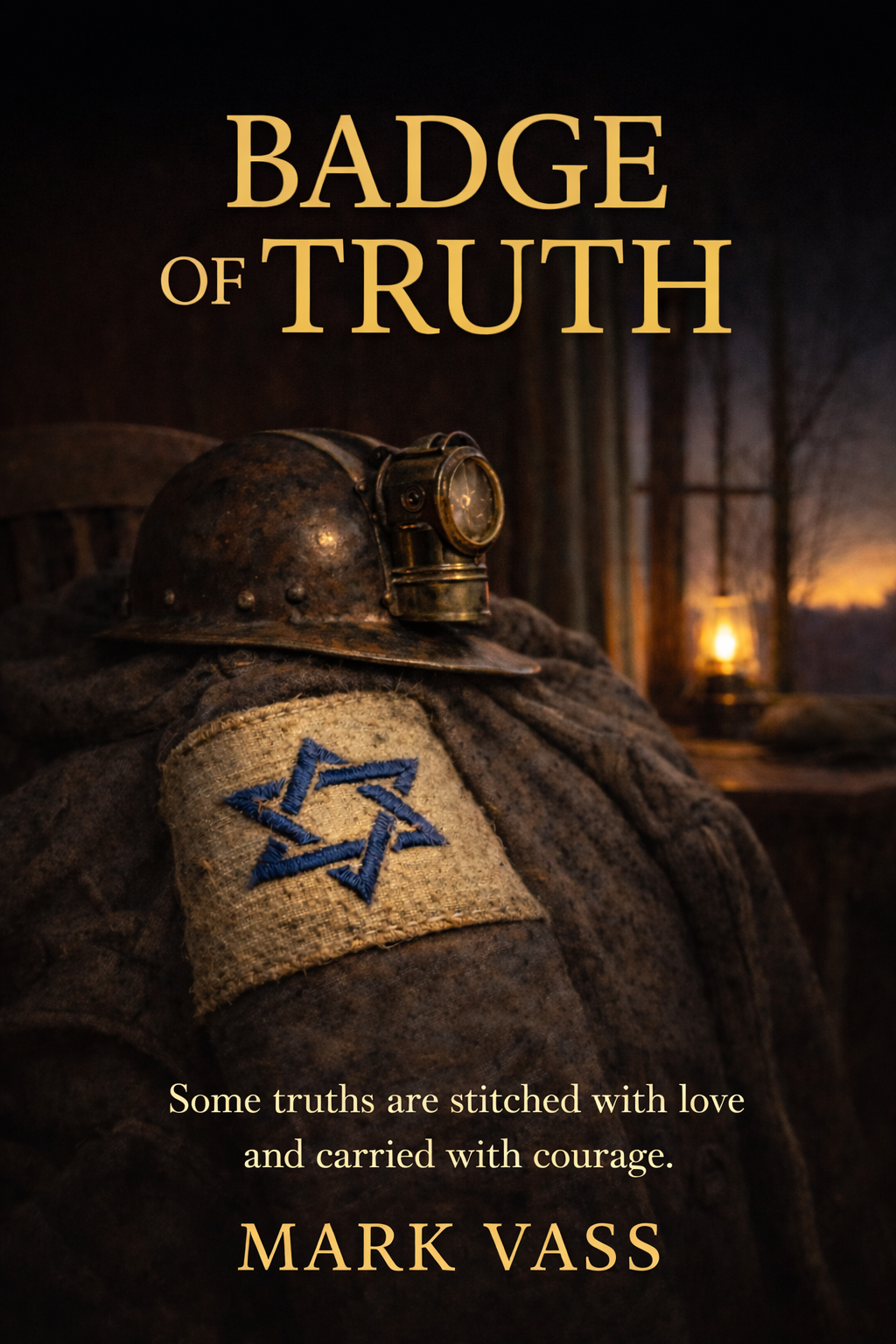

STORY INTRODUCTION

In a coal mining hollow where danger is ordinary and silence is a form of survival, a twelve-year-old girl is entrusted with a truth that cannot be hidden.

As daily life continues under the shadow of the mine, Abigail learns that identity is not something declared, but something carried. When loss comes to Coalburn Hollow, she is forced to stand visibly, honestly, and without illusion—choosing not escape, but presence.

Told with quiet authority and restraint, Badge of Truth is a coming-of-age story about bearing what cannot be undone, staying where life is hardest, and learning how to live without looking away.